Report 20.3: Joan, in Pieces

Boxes, letters, datebooks and a quiet collapse of narrative inside the NYPL archive.

PART ONE | PART TWO | PART THREE

[BOX 235: FOLDER 3]

Dear Mother and Daddy, I just got back from dinner and found your letter — thank you so much. I was really glad to hear from you. I’ve been feeling a little homesick the past couple of days, I guess just tired and sort of let down after the excitement of moving in and getting started. But things are settling down now.

[INTERIOR LIBRARY, MORNING]

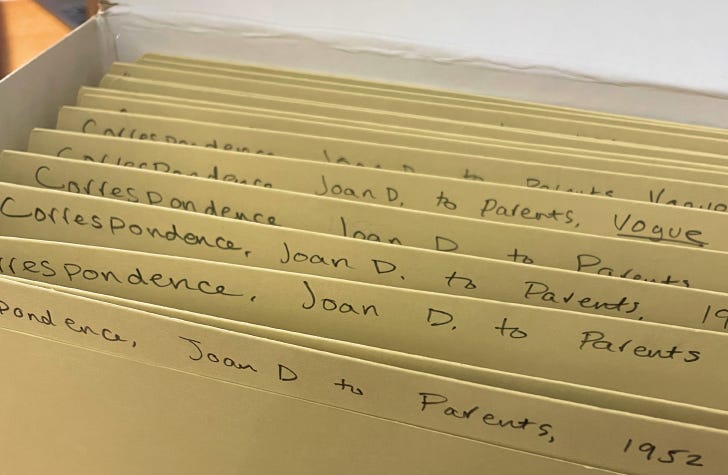

The letters Joan Didion wrote home while attending Berkeley are some of the earliest examples of her writing in the Didion / Dunne archive, where I am now, with a pile of them on the desk in front of me. It’s just the two of us, together, alone with our thoughts.

Except for family, executors, and the small staff here at The New York Public Library’s Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, I’m likely the first person to hold these letters.

Well, unless Lesley M.M. Blume, who was here when I arrived, already went through them all. I can’t help but look over at her, again, typing away on her laptop. No wonder I haven’t heard from Michael Hainey. If AIR MAIL is running something about the archive, it’s likely being written right now, just a few desks away.

For weeks I allowed myself to believe something was leading me here. Not fate, exactly, but a connection between events that I could see and follow. The path seemed to have meaning. It seemed to have purpose. But the closer I get to Joan, the less clear my reason for being here becomes.

All I can do is keep reading. So I keep reading.

She seems just as lost as I do. Which is of some comfort. But it quickly becomes apparent Joan Didion knows exactly who she is and where she’s headed. Her letters from the 1950s are full of the vulnerability you’d expect from someone away from home for the first time. But the slightly theatrical voice and emotional framing that will underpin the career-defining essays to come is already here.

Instead of dates, each one is staged with dramatic cues in the top right hand corner that put you in the director’s seat of her imagination.

NEXT DAY AFTER DINNER

TUESDAY AFTERNOON

LAST NIGHT IN BIG CITY

By the time she leaves California for New York in the final months of her program, the letters take on an even more aesthetic quality, on letterheads that speak with their own quiet authority. The Barbizon, a women-only hotel for aspiring professionals where she stayed during her Mademoiselle practicum. Midston House, a towering uptown residence where she lived while working at Vogue. When she fired off letters to her parents on Condé Nast internal memo sheets or stationery from hotels in Boston and Montreal it seemed to say as much about her progress as the words she wrote did. At 21, style for her was already part of the package.

Another folder in the box takes me to 1964. Joan is back in California now, and married to John Gregory Dunne. They live in a dilapidated Hollywood Mansion, then a Malibu beach house. In 1966 the couple adopts a baby girl and names her Quintana Roo Dunne.

Joan is the mother now. The last folder of letters aren’t to her parents, but to her daughter. When I finish going through them, it’s the 80s. Only one letterhead appears: JOAN DIDION DUNNE, engraved in all caps. No borrowed stationary is needed. From homesick daughter, to mother and cultural authority, she’s become a brand entirely her own in a single archival box.

I lean back into the curve of the library’s heavy hardwood chair with the last letter in front of me. All I can do with what I’ve just read is stare into the void of my own existence. I’m in an institution that preserves the past as a source of knowledge to learn from, but what is chosen for preservation and what is left to vaporize into the atmosphere of memory is an academic choice. This room is a stark reminder of what Joan is, what I am not, what we choose to remember, and how we decide to remember it.

[BOX 256: FOLDER 2]

It is very easy to sit at the bar in, say, La Scala in Beverly Hills, or Ernie’s in San Francisco, and to share in the pervasive delusion that California is only five hours from New York by air.

I came to New York from a Canadian city known for its glass towers set into the natural beauty of mountains and the Pacific Northwest. But I never hear much about that. Instead, all I hear about is drugs. Using them, surviving them, building careers or identities out of them. Making movies about them.

The city’s newest landmark is a back alley named after a former addict that was recently found dead. When I saw the name of his now-pregnant girlfriend, I froze. We were together for several years.

It was from her bookshelf that I took down The White Album and read Joan Didion for the first time. It was from the veranda of The Royal Hawaiian, where the White Album begins, that I sensed her distance. We broke up shortly after returning home.

Only now do I realize the connection. Only now do I realize the reading room I just walked through holds her last name.

I searched the obituaries, desperate for any mention of her. But of course, they were mostly about him. With poetic eloquence they celebrated his creative spirit, his art, his recovery, the lives he saved, the people he inspired.

But in everything they wrote, one thing was left out: how he died.

[BOX 282]

We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices.

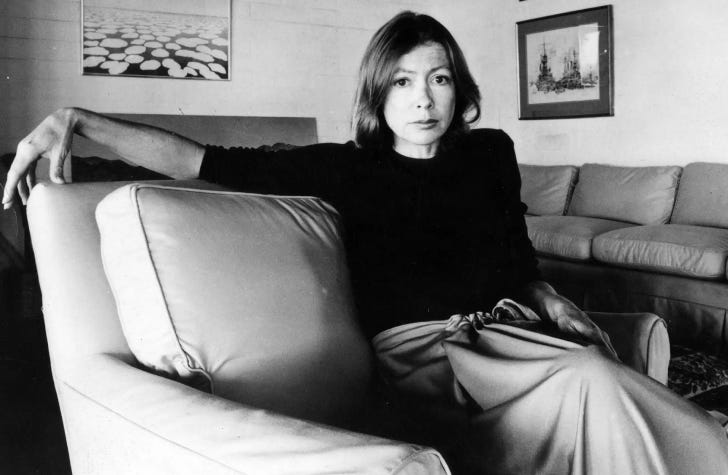

Joan Didion didn’t have to die to become a symbol. When she arrived in Los Angeles at the age of 30, her image as cool observer, woman in control had already been assigned to her. And she was learning to inhabit it. But in private, her mental stability had begun to fray. The gap between her persona and her inner life widened into something harder to reconcile, a quiet undoing she’d soon render with some of her most iconic writing.

Imagine for a moment, even just briefly, everything going your way.

The competitions. The magazine internships. The full-time positions. Want to move to LA? Just put an ad in a local paper, see what happens. Next thing you know you’re living in a house that aligns perfectly with who and what you’re on your way to becoming.

Then you begin to experience things that not only aren’t part of the plot, but but make you wonder if one ever existed.

You sit in a living room with a flower child who is regularly giving her toddler LSD. It’s the “Summer of Love.” You get a phone call about the murder of a movie star and her friends in the Hollywood Hills. The nation turns the cult leader behind it into a celebrity. You watch a presidential candidate assassinated on live television while sitting in a hotel room in Hawaii. The country mourns him as if belief itself had been assassinated. You order room service.

You read about someone who died and left a woman you once loved alone and pregnant. An alley is his legacy. Reality is somewhere else.

And if you’re a writer, you try to pull the pieces together, to impose a sequence, a logic, a reason.

[BOX 16: FOLDERS 9-11]

I went to San Francisco because I had not been able to work in some months, had been paralyzed by the conviction that writing was an irrelevant act, that the world as I had understood it no longer existed. If I was to work again at all, it would be necessary for me to come to terms with disorder.

But what if you can’t?

You get another box.

While I smile enthusiastically along to the now-routine lecture on proper handling of Joan’s things, I notice Lesley M.M. Blume has stopped working to chat quietly with some of the other staff. They’re gathered around her, smiling with enthusiasm at what she’s saying. Something about a flight from L.A. this morning, just to be here — first.

I sign for the box and head back to my desk, which forces me to walk past hers. A hush falls over the small group as I pass by. I can’t bear to look.

Are they whispering about my request to see Box 336? It has a necklace worn by Joan: Denied.

Box 336? With a lock of her hair from the 1960s: Denied.

Boxes 332 through 335 contain unlisted materials, not to be opened until 2050. (At the time, I thought, why not ask. I’ll be writing for AIR MAIL.)

No response.

Editor’s note: Looks like you’re stuck with us.

This new box has only three folders in it. Each one fat with the thick spine of a datebook inside. One for 1969, 1972, and 1973, arguably the Didion Dunne’s most prolific time in California.

Times and locations for shooting Play It As It Lays, a 1972 film based on Joan’s earlier novel, the screenplay for which she and Dunne adapted together. Luncheons and dinners at restaurants almost every other day, many at La Scala. Income statements, doctor appointments, incoming and outgoing flights. A Uriah Heap concert.

I visit the solemn man for another box. Lesley hasn’t left her desk once. This one has an endless pile of ephemera pulled from Joan and John’s upper east side apartment. Dinner menus. Invitations to parties and weddings, including Quintana’s. Anna Wintour’s book launch. Swifty Lazar’s Oscar party. Newspaper clippings. Holiday cards. Book cover proofs.

Then, in a folder all by itself: an 8x10 black-and-white photo of Joan in front of a waterfall in Honolulu, taken by Quintana. There’s an open warmth in Joan’s expression, a kind of ease I’ve never seen in any other photo of her.

On the back, a handwritten message:

For Dad— I figure every man should have a nice photo of his wife over his desk. Happy Father’s Day! I love you! Q xx 20 June ’93 Sunday New York

[BOX 44: FOLDER 6]

I continue opening boxes. I find more faded and cracked photographs than I want ever again to see. I find many engraved invitations to the weddings of people who are no longer married. I find many mass cards from the funerals of people whose faces I no longer remember. In theory these mementos serve to bring back the moment. In fact they serve only to make clear how inadequately I appreciated the moment when it was here.

How am I supposed to make sense of all this? My four hours is almost up and I’ve only made it through a few boxes. There are still hundreds. With more folders. More fragments. Millions of moments and interactions frozen in every static medium the 20th century could offer. Renderings of time that now carry a kind of heartbreaking nostalgia because we know that’s all they are—representations—of something we can no longer experience. Joan turned that devastation into a bestselling novel. Lesley M.M. Blume might be doing the same. I’m still at this desk, wondering what I’m doing, not only in this room, but in this city.

It’s becoming increasingly clear. There will be no preservation in a public institution. No solemn man to police the handling of my things. No filthy back alley set into the natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest named in my memory.

These words will simply cease to exist. They will save no one.

[ANOTHER LINKEDIN MESSAGE TO MICHAEL HAINEY]

Hi Michael. I’m at the archives. It’s been overwhelming and kind of emotional tbh. Lesley M.M. Blume is here, too. Is she writing about Didion for AIR MAIL? Maybe it’s better that way. I don’t think this is my moment.